How to Use Music to Stimulate Creative Thinking

Music Hall. Katowice, Silesian, Poland. Photography by Radek Grzybowski.

By Donald M. Rattner, Architect

“Music has charms to soothe a savage breast,” wrote the English playwright William Congreve in 1697. More than 300 years later, we continue to appreciate the power of music to modulate our emotions. But in an era when professional success and personal happiness depend to an increasing degree on our aptitude for invention, it would be equally worth knowing whether the sound of music can make us more creative as well.

According to science, the short answer is yes — with certain caveats. Before we explore those conditions, though, let’s first understand how music influences the mental process by which we conceive new things.

Effects of Music on Mental States

In my previous article for this series, I explained how noise can boost idea formation by distracting us just enough to keep us from slipping into the kind of rational, linear, convergent, and self-aware mindset that hampers original thinking when brought into the creative process too soon.

Instead, as I described, noise helps us remain within a divergent frame of mind. Divergency is an umbrella term for the abstract, liminal, and freewheeling style of mental processing that gives rise to moments of illumination and creative breakthroughs.

Music room. Westchester, New York. Interior design by Robin Baron Design. Photography by Phillip Ennis. From the book Your Creative Haven by Donald M. Rattner (Skyhorse Publishing, 2019).

Not surprisingly, researchers have found that music can produce a similarly distracting effect. One study, for instance, found that driving while music is playing can substantially diminish the driver’s attention. And why wouldn’t it? At a basic level, music, like noise, is a form of aural stimulation. That both music and noise could draw a portion of our finite supply of attention away from the creative task at hand seems self-evident.

But music is not noise (at least, not the kinds of music I’m dealing with here). Noise is atonal and sonically irregular; music, regardless of genre, has harmony, pitch, tempo, timbre, order, and structure. We dance to music, sing to music, laugh and cry to music because of how our brains are wired. The background chatter in a coffee shop, which is the sort of audio input the noise researchers held up as a model of effective idea stimulation, will never evoke these kinds of emotional reactions.

We also don’t listen to noise for its own sake.

So what does listening to music offer as a creativity enhancer that the everyday din of a busy environment does not?

For starters, it helps induce mind-wandering.

Studio. Marblemount, Washington. Architecture by David Coleman Architecture. Photography by Ben Benschneider. From the book Your Creative Haven by Donald M. Rattner (Skyhorse Publishing, 2019).

Mind-wandering is a mental state in which we detach ourselves from the activity at hand, leaving our thoughts free to roam without conscious direction. No longer constrained by the need to focus attention on a problem to be solved, our minds are more likely to ruminate about the future, experience random collisions of ideas, indulge in imaginative fantasies without risk of adverse effect, and take a big-picture view of the world—all of which foster the development of original insights.

Mind-wandering can be initiated willfully, such as when we let ourselves enter into a daydream state. It can also be induced as a result of external stimuli disrupting or diverting our train of thought. Music can do both—and give us pleasure, to boot.

Which brings us to a second, uniquely contributing factor in music’s ability to heighten creative performance: Music makes us happy, relaxed, and less stressed. Happiness, stress, and creativity are intertwined; the happier and less stressed we are, the more creative we tend to be (and vice versa).

That’s not an anecdotal observation, either. Psychologists have found evidence that happiness induces distractive mind-wandering and, by extension, divergent thinking, whereas negative emotions facilitate laser-like attention—that is, convergent thinking.

No wonder Friedrich Nietzsche once said, “Life without music is a mistake.”

Photography via Wikimedia Commons.

Picking the Right Music

So far, I’ve dealt with music as a generic category of sound. Music, of course, has taken extraordinarily diverse forms across cultures and throughout history. Even within the same genre or tradition, music’s potential range of expression is enormous.

It’s natural to wonder, then, whether it matters what kind of music you listen to when you’re looking to optimize creative productivity.

Research indicates that it does. Here are some of the things research suggests you look for in a track when putting together your creativity playlist:

It’s Familiar

Imagine lying awake in bed with the lights out just before falling to sleep. Suddenly, you hear an unfamiliar noise. Your natural reaction is to become more alert: Your eyes open, and you train your hearing toward the presumed source to figure out whether it’s a threat or harmless.

If you assess the noise to be a threat, your stress levels probably rise, and the adrenaline starts to kick in. Congratulations! Your mind has now entered full sensory alert — exactly the opposite of the distracted mind-wandering state associated with creative thinking. But that’s okay, because your immediate goal in this situation is self-preservation, not creative expression.

Living room detail. Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Architecture and interior design by Richard Davignon and Doris Martin for Davignon Martin Architecture + Interior Design. Photography by Eymeric Widling. From the book Your Creative Haven by Donald M. Rattner (Skyhorse Publishing, 2019).

The same holds true with music. Listening to music you’ve heard before (or by an artist you recognize, or in a genre you’re familiar with) relaxes us precisely because it poses little threat of the unknown.

As former Eurythmics band member Dave Stewart points out in his book The Business Playground: Where Creativity and Commerce Collide, our affinity for the familiar is built into our neurology: The same areas of the brain (auditory cortex, thalamus, and superior parietal cortex) activated by musical inputs also identify recurring patterns in the physical world. It’s another neural mechanism for staying alive inherited from our caveman days (and still useful today).

There’s an additional problem with listening to unfamiliar or artistically challenging music during periods of ideation: You’re liable to try to make sense of it. Once that happens, the music has become more an object of focused attention than a distraction or inducement to mind-wander.

You Like It

As I remarked above, positive emotions facilitate idea formation, whereas negative emotions facilitate analytic thinking. Listening to music you’re not into leads to unwanted convergency. Find music that puts you (and perhaps your colleagues) in a good mood, rather than leaves anyone feeling annoyed, repulsed, or depressed. (Plus, they’ll like you better for it.)

Photography via Pexels.com.

It Has Appropriate Tempo and Content

Various studies have measured the effects of different musical tempos on creative and analytical task performance. The general consensus appears to be that a lively 60 to 80 beats per minute is optimal for stimulating creative excitement. As with all prescriptions, this figure is likely to vary depending on the nature of the creative problem being solved, personal preferences, and whether you’re using music to kick off a creative session or as an ongoing background track.

Other studies suggest that instrumental music might be a better choice for your playlist than music accompanied by lyrics, since words can capture your attention. Besides purely instrumental pieces, alternatives include opera in languages you don’t understand, rock and roll tunes with unintelligible lyrics (plenty to choose from), and songs you already know the words to.

The Beatles in New York, 1964. Photography via Pixabay.com.

It’s Task Appropriate

If you’re sitting down to write elegiac poetry, it’s probably not the time to fire up Wagner’s “Flight of the Valkyries.” On the other hand, to kick off a multimillion-dollar advertising campaign with a group brainstorming session, you might choose something a little more uptempo than, say, “Michelle” by the Beatles.

It’s Played at Optimal Volume

The researchers who discovered the positive influence of noise on creativity found that subjects boosted their test scores only when the soundtrack played at 70 decibels — about the clatter of a running washing machine. Louder soundtracks interfered with basic cognitive functioning; less-audible stimulants were too faint to be sufficiently distracting.

While I haven’t seen similar data specifically relating to music, I suspect an optimal volume falls in the same range as noise, though perhaps with greater potential variation depending on musical genre and context. Guns N’ Roses probably works best with a little more juice, and folk, jazz, and classical music closer to the recommendation of 70 decibels for noise.

Photography via Pexels.com.

Playing a Musical Instrument to Boost Ideation

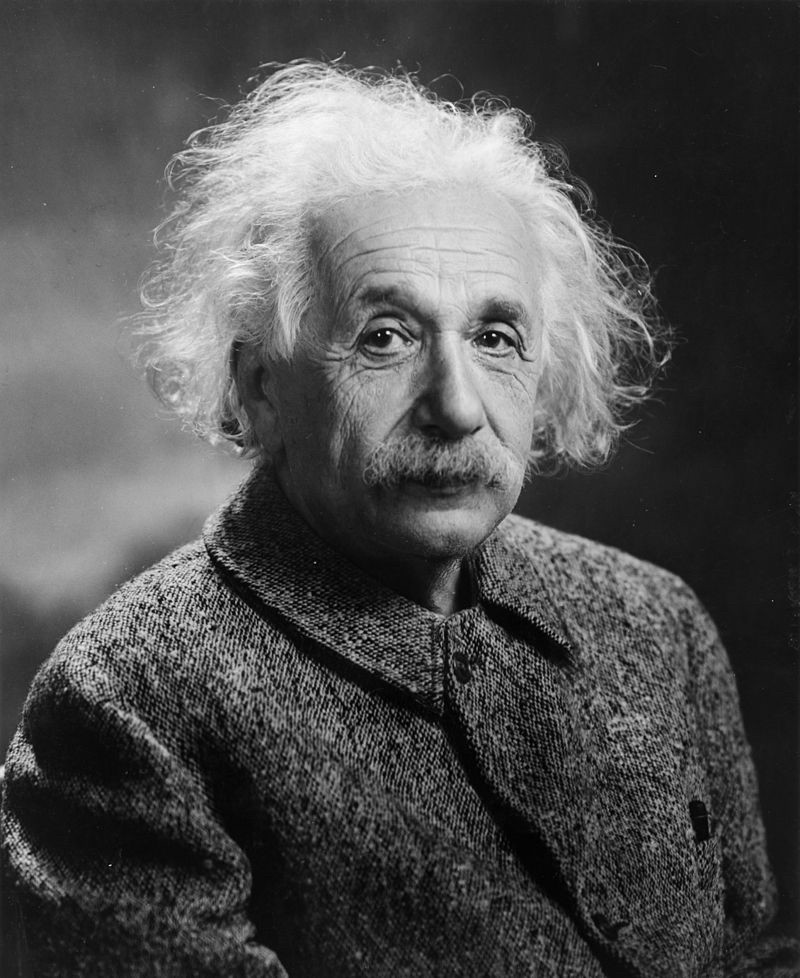

It’s no coincidence that two of the greatest problem solvers of the past century and a half — one fictional, the other factual — routinely pulled out their violins when they encountered creative blocks.

Both Albert Einstein and Sherlock Holmes were legendary for leveraging the magic of music to boost problem solving not only by listening to it, but also by creating it on a musical instrument.

Albert Einstein. Photography via Wikimedia Commons.

Einstein in particular saw making music as integral to his professional and personal self. “If I were not a physicist,” he once said, “I would probably be a musician. I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music.”

Music also played directly into his problem-solving methodology. Einstein told Gestalt psychologist Max Wertheimer that he relied on images, feelings, and musical architectures, rather than conventional symbols or mathematical equations, to arrive at new ideas and scientific breakthroughs.

There are several possible reasons why musical performance can lead to creative breakthroughs. Some are owed to the same factors deduced from studies of noise and music listening: constructive distraction, incentive to mind-wander, and positive mood arousal.

Others are specific to the act of playing an instrument. For instance, stepping away from a problem by taking up a completely different activity is a well-known method for giving your conscious brain a rest and letting back-of-mind functions work through the problem on their own.

Another is that body movement is often an effective creativity catalyst. That’s why taking a walk, exercising, and behavior that moves the hand or gets the blood flowing have been observed to improve idea generation.

And finally, there’s the fact that practicing and performing on a musical instrument stimulate and strengthen multiple brain operations, including those that forge neural connections across its various parts. That’s not an insignificant fact. Creativity often emanates from the fusion of disparate ideas, just as it is thought to derive from synaptic connections made on a neural level.

Conclusion

Music offers a potentially powerful tool for elevating your capacity for holistic thinking to peak levels. Together with the perception of space, light and lighting, and noise, music is one more factor to manipulate to your advantage when shaping your ideal creative environment.

• • •

Donald M. Rattner is an architect and educator exploring the intersection of creativity and physical space. His book My Creative Space: How to Design Your Home to Stimulate Ideas and Spark Innovation has won four awards and has been ranked an Amazon Best Seller. All photographs credited to the book are courtesy of the designers and photographers. A version of this article first appeared on Better Humans.